Researchers steering a remote-controlled submarine around the world’s deepest known hydrothermal vents have collected numerous samples from sunless depths of the Caribbean Sea where blazing hot, mineral-rich fluid gushes from volcanic chimneys that look like gnarled tree stumps.

Researchers steering a remote-controlled submarine around the world’s deepest known hydrothermal vents have collected numerous samples from sunless depths of the Caribbean Sea where blazing hot, mineral-rich fluid gushes from volcanic chimneys that look like gnarled tree stumps.Jon Copley, chief scientist for the expedition organized by Britain’s National Oceanography Center, said that he believes that laboratory analysis in the coming months will reveal some new life-forms that have evolved in the pitch-black vent areas of the Cayman Trough, more than 5 km below the sea’s surface between the Cayman Islands and Jamaica.

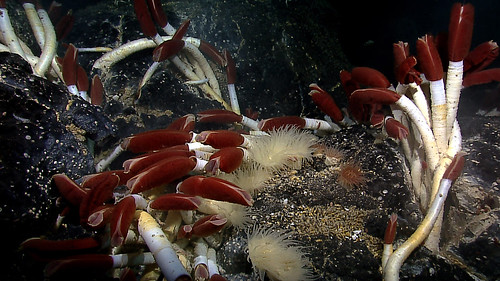

“From body form alone, I am confident that we have found several new species on this expedition: probably a new species of sea anemone, a few species of bristle worms, and some small crustaceans,” Copley said in an email from the RRS James Cook research ship.

The researchers discovered the deepest known hydrothermal vent field and new organisms in the Caribbean trench nearly three years ago.

At a depth of 4,960 meters, the Beebe Vent Field spews out inky, copper-enriched fluids from hot regions below the seafloor into the frigid depths of the sea.

The undersea vents are among the hottest found anywhere on the planet.

The highest sustained temperature that researchers measured was just over 400 degrees Celsius, said Copley, a marine biologist who works at Britain’s University of Southampton.

Besides discovering new life, scientists say the study of the vents could yield a variety of new insights into the geological processes that form and drive them, the physics of so-called supercritical fluids — liquids so hot they act like gases — and the chemical makeup of the ocean’s depths.

Copley said studies of the marine life found in the area should also tell scientists more about how animals disperse and evolve in the dark ocean depths, which cover most of our planet.

Another scientist aboard the ship, Andrew David Thaler, a postdoctoral researcher at the Duke University marine laboratory in Beaufort, North Carolina, said there were abundant populations of some species around the vents, particularly an eyeless shrimp dubbed Rimicaris hybisae that was discovered by the research team in 2010.

“They’re so thick that you often can’t even see the rock beneath because they’re buried in blankets of shrimp,” Thaler said in an email from the James Cook.

Such large amounts of anemones were found at the Beebe site that Thayer said they “look almost like meadows.”

Among other things, researchers recorded images of a slender mineral chimney almost 10 meters tall.

At another site, a mound of minerals formed by the superheated fluid rushing from the vents rises some 30 meters from the seafloor.

They saw brilliant oranges and red colors on the seabed from the bounty of iron, and also blues and greens from copper.

The ultrahot fluid shooting from the vents into the icy cold of the deep ocean creates a smokelike effect and leaves behind pinnacle-shaped structures of metal ore. The pressure — 500 times stronger than the Earth’s atmosphere — keeps the water from boiling.

At the base of this ecosystem are chemical-eating bacteria that draw on the hydrogen sulfide and methane erupting from the vents to make food.

Unlike other living things, the organisms that inhabit the dark vent areas do not depend on photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert sunlight into energy. Instead, chemosynthetic bacteria form the base of the food chain.

To see what scavengers might show up, a big slab of pork was dropped into depths some distance away from the vents.

Cusk eels about 1.5 meters long and scavenging crustaceans called amphipods made short work of the meat offering, according to the expedition scientists.

“The fact that it has been so quickly eaten means that, despite being very nutrient-limited, the deep sea can still support animals capable of exploiting the random occurrence of large carcasses sinking to the seafloor,” Thayer said.

Source: The Japan Times

Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Explorer via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)